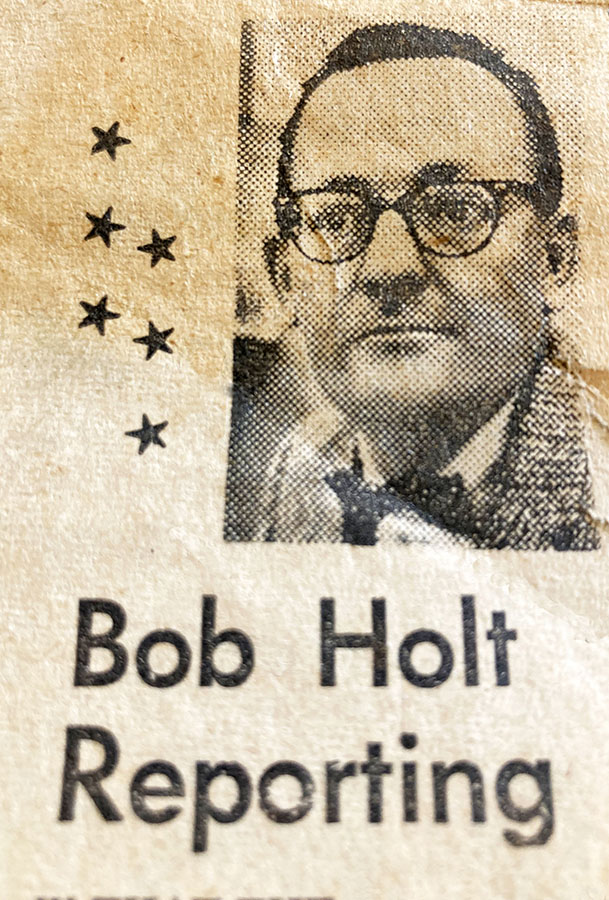

Sixty-five years ago, my little sister Betsey survived a critical illness with her usual aplomb. My parents were terrified at the time and didn’t say much about her condition. I remember my father telling me the morning after her surgery that she would be fine, although he didn’t sound like he was very confident. He wrote the following column about a week later. Betsey beat the 1958 medical odds to celebrate her seventy-second birthday today. Happy birthday, Betsey. Cheers to many more.

It was a typical Sunday evening at home. I was reading. My wife was doing something in the kitchen. The children were watching “Lassie” on TV.

Timmy, the little boy who is Lassie’s current master, had been stricken with appendicitis on the TV screen, which greatly excited the curiosity of our daughter Betsey, age seven.

How do they get his appendicitis out? she wanted to know.

“It’s appendix,” I said. “They cut him open and take it out.”

“Did they put him to sleep?”

“Yes.”

“With a shot or a pill?”

“A shot, I think, or maybe ether.”

“What’s ether?”

“Well. It’s stuff that puts you to sleep.”

“Does he get the shot in his arm or in his seat?”

“Hard to say,” I said.

“You know Daddy,” she said, “I’ve got a pain in my side, too.”

Her little face, upturned, was earnest.

Later, I remarked to my wife, “Some imagination that kid’s got. Maybe she’ll be an actress.”

That was on Sunday.

Monday afternoon, late, my wife phoned. I was in bed, under the impression that I was sick with a cold. But my symptoms vanished with her words.

“I’m at the doctor’s office. Dr. Perry thinks Betsey may have appendicitis. I’m taking her right to the hospital.”

At that point, I was wishing I had not been so graphic with my description the night before.

Betsey seemed big when she walked into the hospital and gave the lady at the desk her name. But she looked mighty small on that big white gurney being rolled to surgery.

The wait seemed interminable. Outside, it was getting dark. Finally, the elevator brought her down again.

Dr. Stephen Chess, wearing a surgical gown the color of pea soup, was grave-faced. Her appendix had been ruptured for more than a week.

A week! I was thunderstruck. The medical folklore of my youth said that a person died within a few minutes after their appendix burst. But Betsey had hardly been ill. A complaint about a stomachache once or twice. But don’t children always have stomachaches?

Parents of sick children become acquainted fast during their long vigils. I learned about little Patty, age five months, a beautiful baby who needs a blood transfusion every two weeks. Nobody knows where the blood goes. Or Corey, a two-year-old boy, who is allergic to thirty-one things, including milk. Maybe his name is spelled Cory – at the time I was a father not a reporter, and I wasn’t worrying about how to spell names.

And then there are the T & A patients – tonsils and adenoids. The hospital grows a new crop of these youngsters every two days. And at Easter vacation they are especially plentiful. Some children go to Disneyland at Easter, while others get their tonsils out.

They’re very chipper in the evening when they come in. Next day, they are sick with the smell of ether about them. The next morning, they go home, and that night some new ones take their place.

Betsey, as an old-timer of a week, looked somewhat patronizingly on these transients, like a regular Army man eying a group of draftees.

Betsey’s case has now settled down to a battle of antibiotics vs. infection. After the first few days, her complaint wasn’t that her operation hurt, but that her seat did. In a little child, you rapidly run out of places to stick needles.

Through it all, she has never shed a tear, and is proclaimed by doctors, nurses and the serene-faced nuns as the very model of a model patient.

I would like to think that, under similar circumstances, I could do as well.