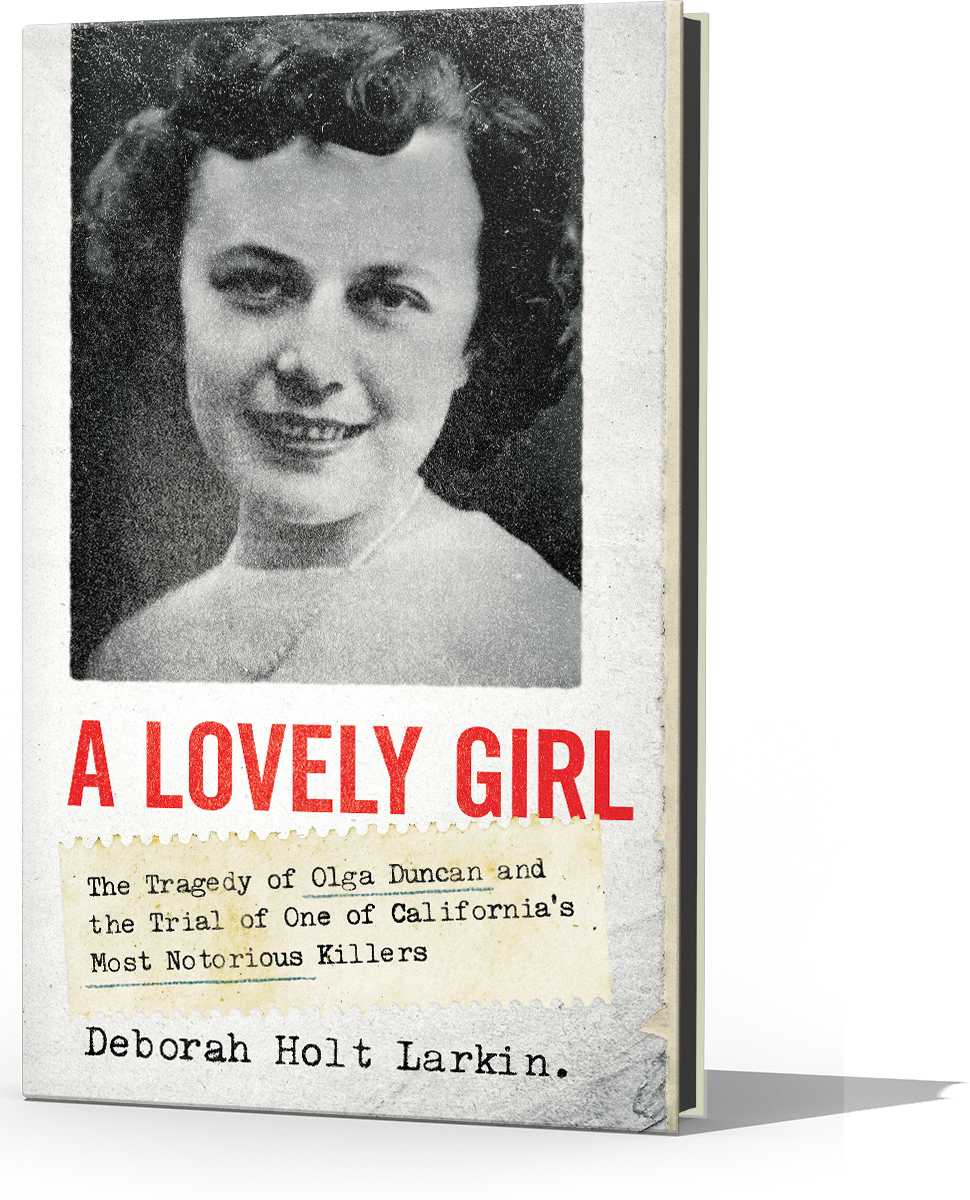

I spent many years researching the Olga Duncan murder case. I had my father’s files to work from, along with my memories of our numerous discussions about what he always referred to as the remarkable Duncan case. I’d also written some notes about his opinions of Olga’s bizarre, brutal, and bumbling killers and, of course, I had my own recollections of my over the top obsession and anxieties about Olga Duncan’s horrible murder.

But it was the 5,000 pages of Elizabeth Duncan’s trial transcripts that transported me back to the 1950s and inside the majestic marble floored white-pillared Ventura County Courthouse. I time traveled into the mahogany-paneled courtroom and imagined myself sitting with residents from all over Ventura County lucky enough to find a seat in the packed gallery. At 10:00 am on February 24, 1959, when Judge Charles Blackstock called court to order, I visualized it all in black and white, the men in their single-breasted suits, bow ties and fedora hats. I listened to the pointed questions from confident district attorney Roy Gustafson and the smooth-talking insinuations of renowned LA criminal defense attorney Ward Sullivan. Their voices came to life across the 60-year time gap—the nervous stutters of the prosecution witnesses, the mutterings of dozens of reporters in the hastily expanded press section, and especially the startling shrill and frequent outbursts of the defendant, Elizabeth Duncan.

Sometimes, when the spectators inhaled sharply at shocking witness accounts or laughed at unbelievably crazy testimony, I gasped and snorted right along with them. Judge Blackstock warned us quiet with a stern look or, if necessary, threatened that he would clear the courtroom. And even though I always knew the outcome of the trial, I was so caught up in the drama unfolding on the pages of transcript that I sometimes worried about a mistrial when things went wrong.

Unlike many murder trials today, Mrs. Duncan testified in her own defense. She called the prosecution witnesses and the DA liars, denied her guilt, and hurled defiance at all her accusers. She told the jurors that she was the real victim in this story. Frank Duncan insisted that his mother was innocent and testified that she was the best mother a boy could ever have. While reading these transcripts I stiffened and covered my mouth as the confessed hired killers described, in matter-of-fact tones and excruciating detail, the step-by-step process of how they kidnapped and murdered an innocent young woman.

I could have never written A Lovely Girl without the the serendipitous intervention of Ventura attorney Robert McSorley. Bob had been a thirteen-year-old newspaper delivery boy at the time of the trial and, like me, had developed a keen interest in the front-page stories in the newspapers he delivered on his bicycle every day. The Duncan transcripts had disappeared from the Ventura DA’s office sometime in the 1960s, after the case was fully adjudicated. Over the years, the DA’s office conducted searches for the missing transcripts of the most notorious case ever prosecuted in Ventura County in order to preserve these files for history. But nothing turned up until a grown-up Bob McSorley, by then a partner at a Ventura County law firm, stumbled across the lost Elizabeth Duncan trial transcripts gathering dust on the top shelf of his law office’s library in 2001. And because of his boyhood fascination with the story, Bob understood the significance of what he’d found.

The rest of the story to follow!